Smith and developer John Hoge for bragging rights to Seattle’s tallest and most extravagant skyscraper. The tower’s height and design were sparked by a friendly competition between L.C. The various designers worked to make the Smith Tower a prime office building, with an elaborate, high-ceilinged lobby with polished marble walls and ornate decorations. In addition, the general contractor and structural engineer were based in New York City.

Yet much of the building hailed from outside the city and state: the steel was manufactured by the American Bridge Company of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and the terra-cotta cladding came from California. Davis Company of Seattle began assembling a 7.97-million-pound fireproof steel frame, which was reinforced by 50 concrete support columns. The Smith Tower began construction in November 1911 when the E.E. An 8-foot glass globe was perched at the cap’s pinnacle, serving as a beacon to ships in the Puget Sound. A decorative masonry balustrade also wrapped around the base of the pyramidal cap, each side of which featured 6 pointed-arch window openings. To help set it apart from the predominantly brick-and-stone buildings that marked the buildings of surrounding Pioneer Square, the architects gave the tower a predominantly white terra-cotta exterior that rose above a two-story base made of local granite. Walker Gaggin) specified what was essentially a two-tower form, with a thin, 11-story tower with a pyramidal cap mounted atop a blockier, 24-story base with a cornice-a form that had begun to grace the New York skyline but was unknown in the western United States. To provide the building with architectural distinction, Gaggin and Gaggin (founded by the brothers Edward Gaggin and T. Yet the firm was known to the tower’s developer, Lyman Cornelius (L.C.) Smith, who had made a fortune in the typewriter and gun manufacturing industries and also hailed from Syracuse. The Smith Tower was designed by the Syracuse, New York–based architectural firm Gaggin and Gaggin, whose prior experience did not include any building more than five stories tall.

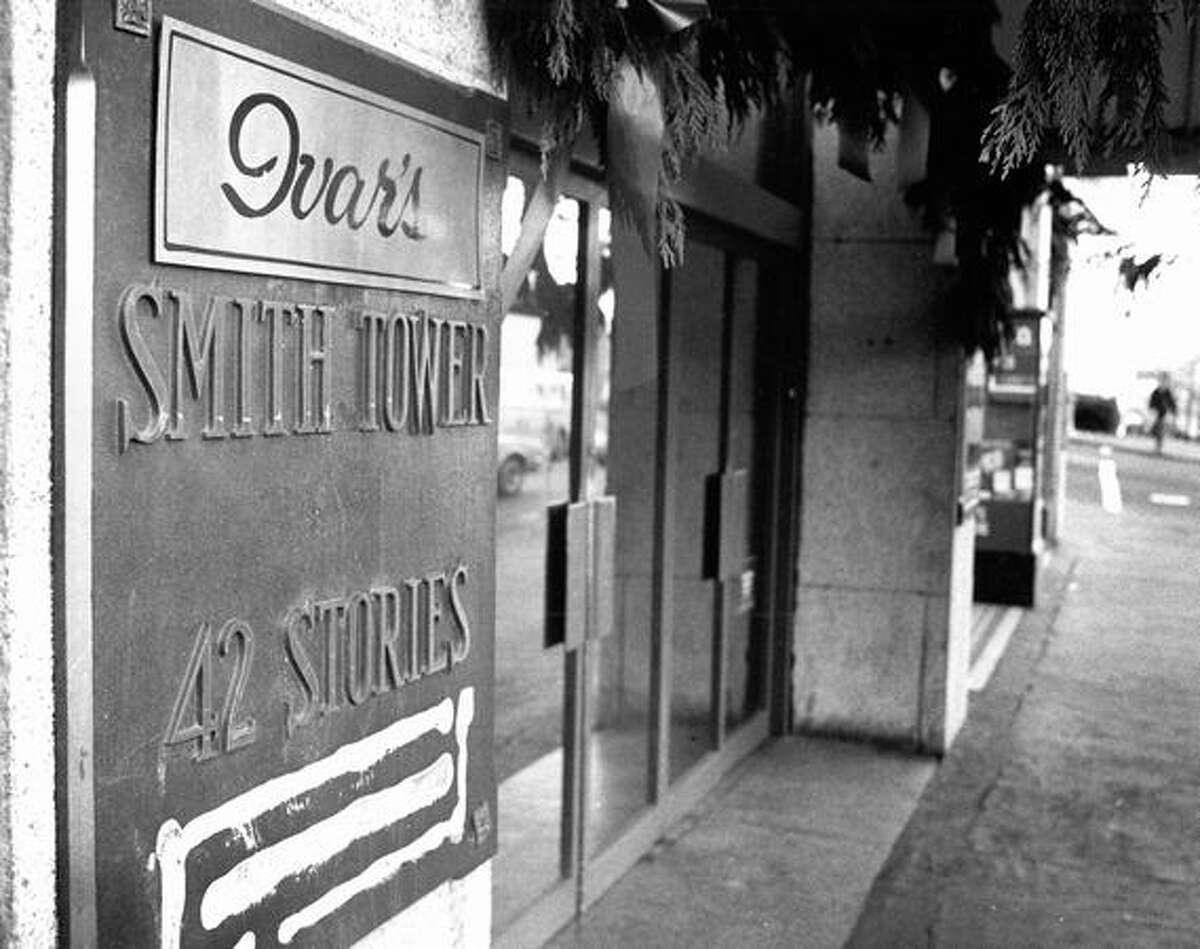

It was also the tallest building west of the Rocky Mountains during this period. For much of the twentieth century, the 462-foot-tall skyscraper, with its distinctive pyramidal roof, more than 2,300 bronze-encased windows, and over 1,400 steel doors was a regular feature on postcards and other images promoting the city of Seattle, and held the title of the city’s tallest structure for nearly 50 years. The building featured retail at the base with offices above, as well as a public, open-air observation deck on the 35th floor extending from what was advertised as a “Japanese Tea Room” but designed loosely following the manner of a Chinese temple with a carved teak ceiling and blackwood furniture. What was promoted as the “highest, finest, and most complete office building in the world outside of New York City” came equipped with several up-to-date amenities including a wireless telegraph, telephones, eight high-speed elevators, and a central vacuum system with “plug-ins” in every office. Smith Building typifies Seattle spirit and growth.” While skeptics have since debunked the myth that the approximately $1.5 million building contained 42 floors at its opening (the number was actually closer to 36), the notion that the Smith Tower served as a symbol for the city’s progress and prosperity has rarely been a point of contention. Underscoring the importance of what was set to become the tallest building west of the Mississippi, one full-page advertisement declared, “The 42-story L.C. Smith Building on Second Avenue and Yesler Way in the heart of Pioneer Square. Leading up to July 4, 1914, advertisements in Seattle’s newspapers proliferated in advance of the grand opening of the new L.C.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)